Three Lessons Henrietta Lacks Taught Us about Clinical Research in the Black Community

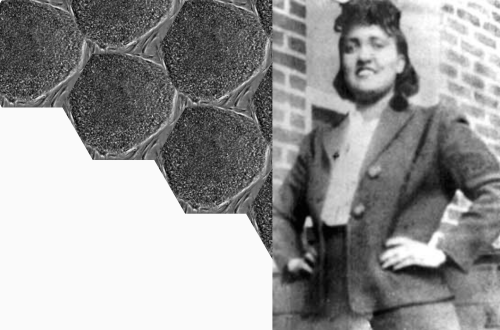

If you had met Henrietta Lacks in 1950, you would have likely been charmed by the 30-year-old African-American woman filled with life and never without her signature red nail polish. She loved to cook—spaghetti was her specialty, and she regularly danced with her children in the kitchen as the red sauce simmered. In 1950, Henrietta would have no idea that an incredible chain of events was about to take place; that her cervical cells would soon be biopsied without her consent, and that long after she passed, those cells would go on to prevent 4.5 billion global infections and 10.3 million global deaths.

Her incredible story matters to everyone in the research sphere today. Here are three big ways Henrietta’s life and cells changed the world.

First: People first in research, always

When Henrietta began to experience unusual cervical pain and bleeding, she went to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, for treatment. Without her knowledge or consent, a doctor at Johns Hopkins took a biopsy of her cancer cells for research purposes. Because Henrietta was an African American woman living in the era of Jim Crow segregation and institutional racism, this lack of consent was sadly quite common. Her cells, later dubbed HeLa cells, were found to be unique in their ability to grow and multiply indefinitely in culture, making them ideal for use in scientific research. But the unethical and controversial nature of their discovery has elevated the importance of privacy and consent, particularly in underrepresented patient populations. What’s worse, her cells continued to be used and commercialized without permission until 2013, when the National Institutes of Health reached an agreement with the Lacks family to give them some control over how Henrietta’s genome is used in future research.

The lesson: research must be conducted in partnership with patients, underpinned in the highest ethical standards. That’s why TFS puts trust and transparency at the heart of everything we do. When communities and researchers build trust, science thrives.

Second: One breakthrough can transform a field

Unlike any other cells researchers saw before them, HeLa cells multiplied rapidly and, importantly, they never died. This unlocked scientists’ ability to speed exploration in massive ways. Since they were discovered, HeLa cells have moved mountains in clinical research, particularly in the fields of two TFS focus areas: oncology and hematology. Let’s explore just a few:

-

- Testing for cancerous cells – HeLa cells were used to discover multiple quick and simple testing methods for cancerous cells that are still used today. With a single HeLa cell, researchers grew colonies that suggested it changes the cell’s surface, allowing tumors to become invasive.

- Blood cancer treatment – In 1964, HeLa cells were used to determine if hydroxyurea could be a potential treatment for blood cancers and sickle cell anemia. Researchers learned that the treatment not only slowed the growth of cancerous cells, but also stopped the misshapen blood cells that occur in patients with sickle cell anemia. The treatment is still used today.

- Cervical cancer vaccines – In the early 1980s, a German virologist found that HeLa cells contained multiple copies of human papillomavirus 18, a strain of HPV later found to cause cervical cancer. Using HeLa cells, he found that the virus spread by turning off the genes that would typically have suppressed the formation of tumors. That insight led to the development of the first HPV vaccine, which reduces incidence of HPV by about two-thirds. The virologist won the Nobel Prize in 2008 for the discovery, and it wouldn’t have been possible without Henrietta’s cells.

- Cancer research – HeLa cells have been used extensively in cancer research, including the discovery of the role of telomerase in cancer cells. Telomerase is an enzyme that plays a crucial role in maintaining the length of telomeres, which are the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes. Telomeres shorten each time a cell divides; however, in cancer cells, telomerase is often reactivated, allowing the cells to continue dividing and growing uncontrollably. Today, that knowledge has led to telomerase serving as a promising target in cancer therapies, and several drugs that inhibit telomerase are now in clinical trials.

- Gene mapping – HeLa cells were used to create the first human genome sequence, which was published in 2000.

- HIV/AIDS research – HeLa cells were used in the development of antiretroviral drugs to mitigate HIV/AIDS.

- COVID-19 vaccines – That’s right, HeLa cells even played a role in the COVID-19 pandemic we are navigating today. The cells were instrumental in speeding discoveries of the vaccines from Pfizer, Moderna, and others.

The lesson: clinical research is, at its core, about the relentless pursuit of hope, and Henrietta’s cells prove how a single breakthrough can snowball and spark many pathways of innovation. This is why research collaborations like those at our TFS Headquarters in Medicon Village are essential to achieve scientific progress. What other breakthroughs are out there awaiting discovery?

Third: We need Black voices and participation in research

Despite the historical injustices and disparities the Black community has endured, medical research very much needs Black representation—and Henrietta’s family agrees. Today, they are preserving her legacy by encouraging African Americans to participate in clinical research, despite their grandmother’s experience. Henrietta’s grandson, David, speaks regularly with patient groups, community centers and conferences about how the Black community must take an active role in research so they do not get left behind—after all, if trial participants are predominately White, there is no way to know if a treatment is effective in other populations. In fact, increasingly studies are showing that an efficacy divide across races does exist; albuterol, for example, the most prescribed treatment for asthma, is less effective in Black and Puerto Rican populations than in White populations. And just this month, the Duke Clinical Research Institute published findings that the tools we use to predict stroke risk are less reliable in Black patients.

The lesson: the wounds of the past are real and valid in the Black community, but with community engagement, we can and must work to bring Black perspectives into the research process. For our trials to be effective, they need to reflect the diverse fabric of our communities, not a single homogenous thread.

In 2021, the World Health Organization honored Henrietta Lacks and the Henrietta Lacks Enhancing Cancer Research Act was signed into law, which aims to ensure that her contributions to science are recognized. The disease that took her life in 1951 is no longer considered the death sentence it once was; it is treatable and often curable, thanks to Henrietta’s immortal cells.

This Black History Month, TFS honors Henrietta Lacks, the woman who not only transformed medical research, but also taught us indelible lessons in ethics, racial equity in research, and the power of hope.

Learn more about our related services and resources:

Contact Us:

Contact us today and join a team that cares about you.